Halford Mackinder developed the theoretical framework for the divide-and-rule strategy of maritime hegemons, which was adopted by the British and thereafter the Americans. Mackinder argued that the world was divided into two opposing forces – sea powers versus land powers. The last land-power to connect and dominate the vast Eurasia continent was the nomadic Mongols, and their collapse was followed by the rise of European maritime powers in the early 16th century linking the world by sea.

The UK and US both pursue hegemonic strategies aimed at controlling the Eurasian landmass from the maritime periphery. Island states (the US being a virtual island) do not need large standing armies due to the lack of powerful neighbours, and they can instead invest in a powerful navy for security. Island states enhance their security by dividing Eurasia’s land powers so a hegemon or an alliance of hostile states do not emerge on the Eurasian continent. The pragmatic balance of power approach was articulated by Harry Truman in 1941: “If we see that Germany is winning the war we ought to help Russia, and if Russia is winning, we ought to help Germany and in that way let them kill as many as possible”.[1] A maritime power is also more likely to emerge as a hegemon as there are few possibilities of diversifying away from key maritime corridors and choke points under the control of the hegemon.

Railroads Revived the Rivalry Between Sea-Powers and Land-Powers

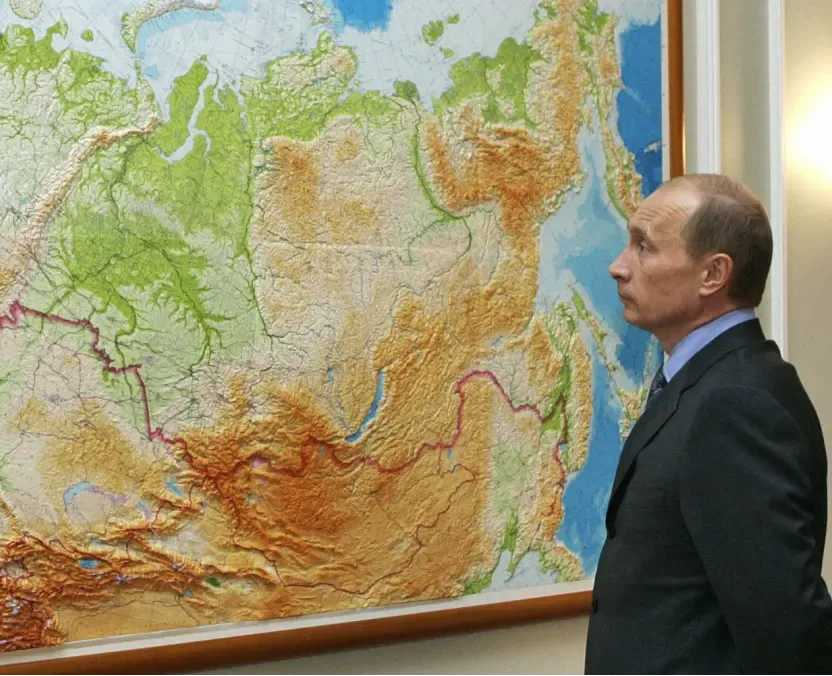

Russia, as a predominantly landpower, has historically been contained and kept weak by limiting its access to reliable maritime corridors. However, Russia's weakness as a large landpower could become its strength if Russia connects the Eurasian continent by land to undermine the strategic advantage of the maritime hegemony.

The invention of intercontinental railways permitted Russia to emulate the nomadic character of the Mongols and end the strategic advantage of maritime powers. Russia’s development of railroads through Central Asia from the mid-19th century resulted in the Great Game as Russia could reach British India. In the final decade of the 19th century, Russia developed the trans-Siberian railroad that challenged British imperial interests in East Asia. In 1904, Mackinder warned:

“A generation ago steam and the Suez canal appeared to have increased the mobility of sea-power relatively to land-power. Railways acted chiefly as feeders to ocean-going commerce. But trans-continental railways are now transmuting the conditions of land-power, and nowhere can they have such effect as in the closed heart-land of EuroAsia, in vast areas of which neither timber nor accessible stone was available for road-making”.[2]

Mackinder warned about the possibility of a German-Russian alliance as it could establish a powerful centre of power capable of controlling Eurasia. Mackinder thus advocated for a divide-and-rule strategy:

“The oversetting of the balance of power in favour of the pivot state, resulting in its expansion over the marginal lands of Euro-Asia, would permit of the use of vast continental resources for fleet-building, and the empire of the world would then be in sight. This might happen if Germany were to ally herself with Russia”.[3]

US Hegemony from the Periphery of Eurasia

Mackinder’s ideas were developed further with Nicolas Spykman’s Rimland Theory in 1942, which stipulated that the US had to control the maritime periphery of the Eurasian continent. The US required a partnership with Britain to control the western periphery of Eurasia, and the US should “adopt a similar protective policy toward Japan” on the eastern periphery of Eurasia.[4] The US thus had to adopt the British strategy of limiting Russia’s access to maritime corridors:

“For two hundred years, since the time of Peter the Great, Russia has attempted to break through the encircling ring of border states and the reach the ocean. Geography and sea power have persistently thwarted her”.[5]

The influence of Spykman resulted in it commonly being referred to as the “Spykman-Kennan thesis of containment”. The architect of the containment policies against the Soviet Union, George Kennan, pushed for a “Eurasian balance of power” by ensuring the vacuum left by Germany and Japan would not be filled by a power that could “threaten the interests of the maritime world of the West”.[6]

The US National Security Council reports from 1948 and onwards referred to the Eurasian containment policies in the language of Mackinder’s heartland theory. As outlined in the US National Security Strategy of 1988:

“The United States' most basic national security interests would be endangered if a hostile state or group of states were to dominate the Eurasian landmass- that area of the globe often referred to as the world's heartland. We fought two world wars to prevent this from occurring”.[7]

Kissinger also outlined how the US should keep the British strategy of divide and rule from the maritime periphery of Eurasia:

“For three centuries, British leaders had operated from the assumption that, if Europe’s resources were marshaled by a single dominant power, that country would then resources to challenge Great Britain’s command of the seas, and thus threaten its independence. Geopolitically, the United States, also an island off the shores of Eurasia, should, by the same reasoning, have felt obliged to resist the domination of Europe or Asia by any one power and, even more, the control of both continents by the same power”.[8]

Henry Kissinger followed the Eurasian ideas of Mackinder, as he pushed for decoupling China from the Soviet Union to replicate the efforts to divide Russia and Germany.

Post-Cold War: America’s Empire of Chaos

Less than two months after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US developed the Wolfowitz doctrine for global dominance. The leaked draft of the US Defense Planning Guidance (DPG) of February 1992 argued that the endurance of US global primacy depends on preventing the emergence of future rivals in Eurasia. Using the language of Mackinder, the DPG document recognised that “It is improbable that a global conventional challenge to US and Western security will re-emerge from the Eurasian heartland for many years to come”.

To sustain global primacy, the “first objective is to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival”, which included preventing allies and frontline states such as Germany and Japan from rearming. The DPG also argued for preserving economic dominance as “we must account sufficiently for the interests of the advanced industrial nations to discourage them from challenging our leadership or seeking to overturn the established political and economic order”.[9]

The US abandoned the agreements for an inclusive pan-European security architecture based on “indivisible security” to mitigate security competition and replace it with alliance systems to divide the world into dependent allies versus weakened adversaries. Zbigniew Brzezinski authored the Mackinderian post-Cold War policies of the US to sustain global hegemony: “America’s global primacy is directly dependent on how long and how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained”. The strategy of preserving US dominance was defined as: “prevent collusion and maintain security dependence among the vassals, to keep tributaries pliant and protected, and keep the barbarians from coming together”.[10]

If Russia would resist American efforts, the US could use its maritime dominance to strangle the Russian economy: “Russia must know that there would be a massive blockade of Russia’s maritime access to the West”.[11] To permanently weaken Russia and prevent it from connecting Eurasia by land, Brzezinski argued that the collapse of the Soviet Union should ideally be followed by the disintegration of Russia into a “loosely confederated Russia – composed of a European Russia, a Siberian Republic, and a Far Eastern Republic”.[12]

The Rise of Greater Eurasia

The US has become reliant on perpetual conflicts to divide the Eurasian continent and to preserve its alliance systems. US efforts to sever Russia and Germany with NATO expansionism and the destruction of Nord Stream have pushed Russia to the East, most importantly toward China as the main rival of the US. The cheap Russian gas that previously fuelled the industries of America’s allies in Europe is now being sent to fuel the industries of China, India, Iran and other Eurasian powers and rivals of the US. The efforts by China, Russia and other Eurasian giants to connect with physical transportation corridors, technologies, industries, and financial instruments are anti-hegemonic initiatives to balance the US. The age of Mackinder’s maritime hegemons may be coming to an end.

[1] Gaddis, J.L., 2005. Strategies of containment: a critical appraisal of American national security policy during the Cold War. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p.4.

[2] Mackinder, H.J., 1904, The Geographical Pivot of History, The Geographical Journal, 170(4): 421-444, p.434.

[3] Ibid, p.436.

[4] Spykman, N.J., 1942. America's strategy in world politics: the United States and the balance of power. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, p.470.

[5] Ibid, p.182.

[6] Gaddis, J.L., 1982. Strategies of containment: A critical appraisal of postwar American national security policy. Oxford University Press, New York.

[7] White House 1988. National Security Strategy of the United States, White House, April 1988, p.1.

[8] Kissinger, H., 2011. Diplomacy. Simon and Schuster, New York, pp.50-51.

[9] DPG 1992. Defense Planning Guidance. Washington, 18 February 1992.

[10] Brzezinski, Z., 1997. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geopolitical Imperatives. Basic Books, New York, p,40.

[11] Brzezinski, Z., 2017. How to Address Strategic Insecurity In A Turbulent Age, The Huffington Post, 3 January 2017.

[12] Brzezinski, Z., 1997. Geostrategy for Eurasia, Foreign Affairs, 76(5): 50-64, p.56.